REVENUE

It's time for an honest conversation about how we pay for cities.

Toronto recognizes that, as a strong generator and beneficiary of economic wealth, it has a responsibility to contribute its financial fair share to Ontario and Canada.

Unfortunately, the current situation is not sustainable. In general, municipalities raise only about 9 per cent of all taxes in Canada. This leaves cities dependent on handouts from provincial and federal governments, which raise the rest.

Unfortunately, the current situation is not sustainable. In general, municipalities raise only about 9 per cent of all taxes in Canada. This leaves cities dependent on handouts from provincial and federal governments, which raise the rest.

|

Given that imbalance, and the public’s resistance to the introduction of new taxes, it is not enough to say Toronto should use the few revenue tools available to it under the City of Toronto Act. Such revenue tools are not progressive and simply cannot raise the amount of money required. A greater share of existing taxation should accrue to Toronto as dedicated, charter-protected municipal revenues. |

Toronto’s share of these taxes should be commensurate with the city’s contribution to Ontario and Canada and with the true cost of providing the programs and services as required by law. The city should control (not just be given or have access to) sufficient revenue to properly fund programs and services within its jurisdiction.

Toronto should also have control of sufficient revenue to properly fund its share of shared programs and services. Such an arrangement would provide stable, predictable revenue and reduce the friction of continually negotiating levels of funding, which fluctuate from government to government. To prevent duplication, the city could piggyback onto current provincial collection systems.

Toronto should also have control of sufficient revenue to properly fund its share of shared programs and services. Such an arrangement would provide stable, predictable revenue and reduce the friction of continually negotiating levels of funding, which fluctuate from government to government. To prevent duplication, the city could piggyback onto current provincial collection systems.

|

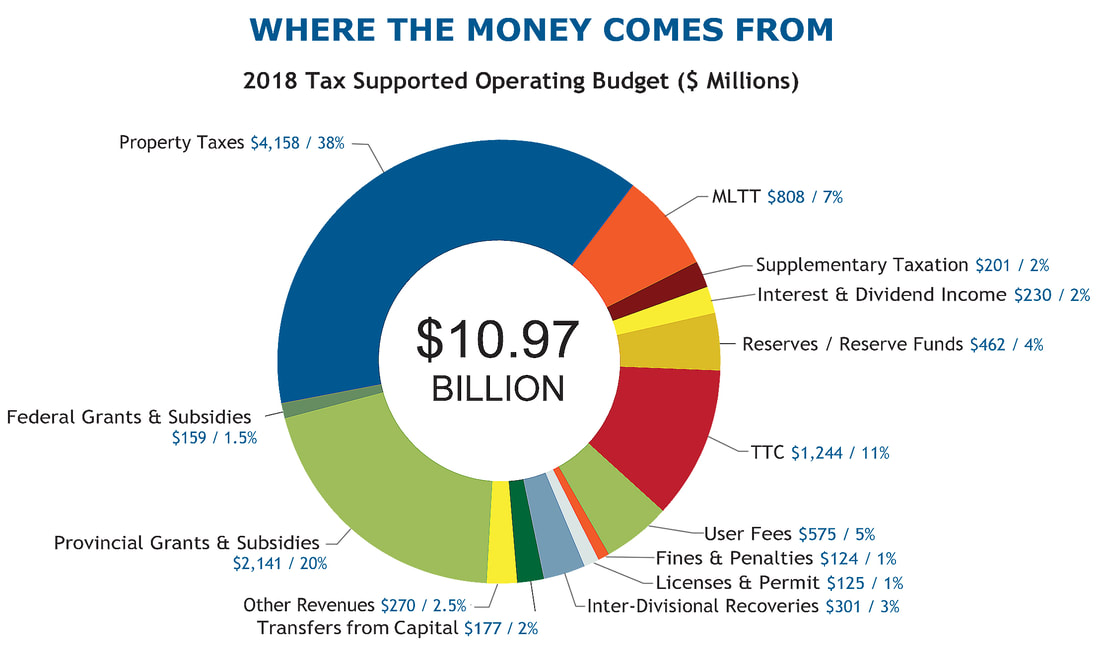

The City of Toronto depends on federal and provincial subsidies for more than one-fifth of its operating budget, yet is prohibited from levying its own large-scale, progressive taxes such as those on sales or income. Instead, Toronto continues to get half of its revenue from property-related taxes and user fees, which are regressive and do not naturally grow with the economy. A very large chunk of property taxes collected in Toronto go directly to the province to fund the education system. |

|

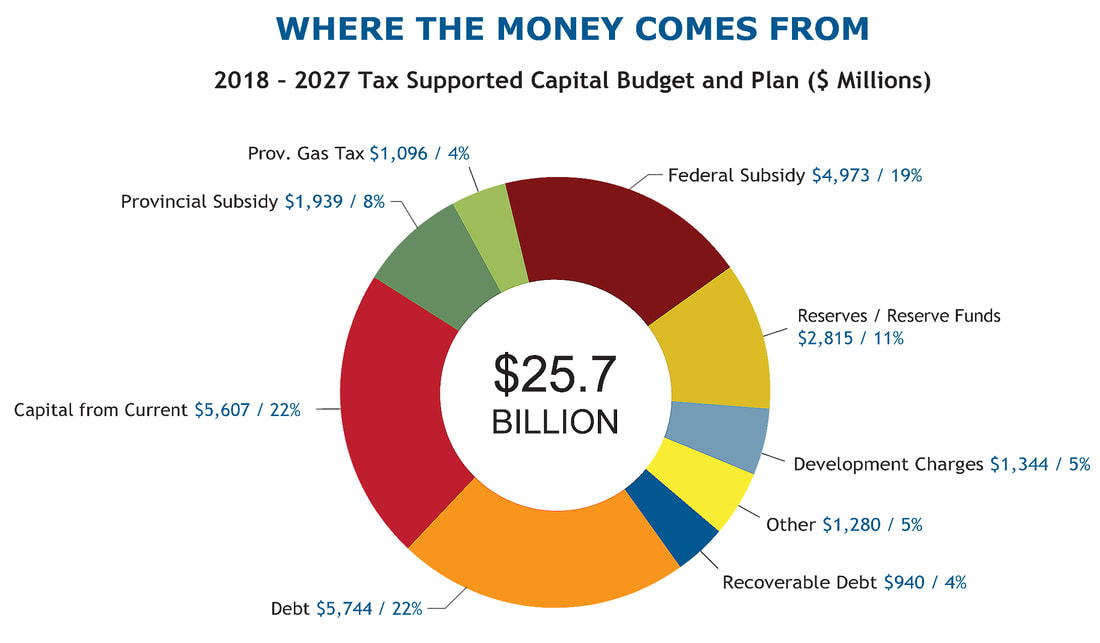

Nearly one-third of Toronto's Capital budget consists of handouts from the province and Canada. While it may seem at first glance that the city is the beneficiary, such a view masks the dependancy this situation creates, and how it hampers the city's independence and its ability to plan spending into the future. Development charges, which help to ensure that city growth pays for the demands on infrastructure and amenities that growth creates, have just been reduced by the province. |

Time and again, Toronto has been deprived of important sources of revenue while expectations of service delivery at the local level have increased substantially.

"Toronto makes up just 6.7 % of all local government spending and only 1.3 % of general government expenditures in Canada. This for a municipal region that serves more than 20 per cent of the Canadian population and is responsible for about the same share of

|

Until 1936, when the province passed the Income Tax Act, Toronto and other Ontario municipalities had statutory authority to levy income taxes. Until 1944, Toronto had the authority to levy corporate taxes.

In both cases, when the province removed these authorities, the city was paid a lump sum in compensation. Given current realities it now seems reasonable that these authorities be returned to the city. Until the creation of the so-called Megacity 20 years ago, the city had control of all the revenue produced by the property tax system, funding both city and Board of Education expenditures. |

When the province took over the education system, it seized control of about half the city’s property taxes for education funding purposes.

The province also has control over many aspects of the property tax system including assessment and the burdens placed on different classes of property, taking much of the important decision-making about property taxes out of the hands of the city. The negative results of this are now being felt by many of Toronto’s property owners.

The province also has control over many aspects of the property tax system including assessment and the burdens placed on different classes of property, taking much of the important decision-making about property taxes out of the hands of the city. The negative results of this are now being felt by many of Toronto’s property owners.

|

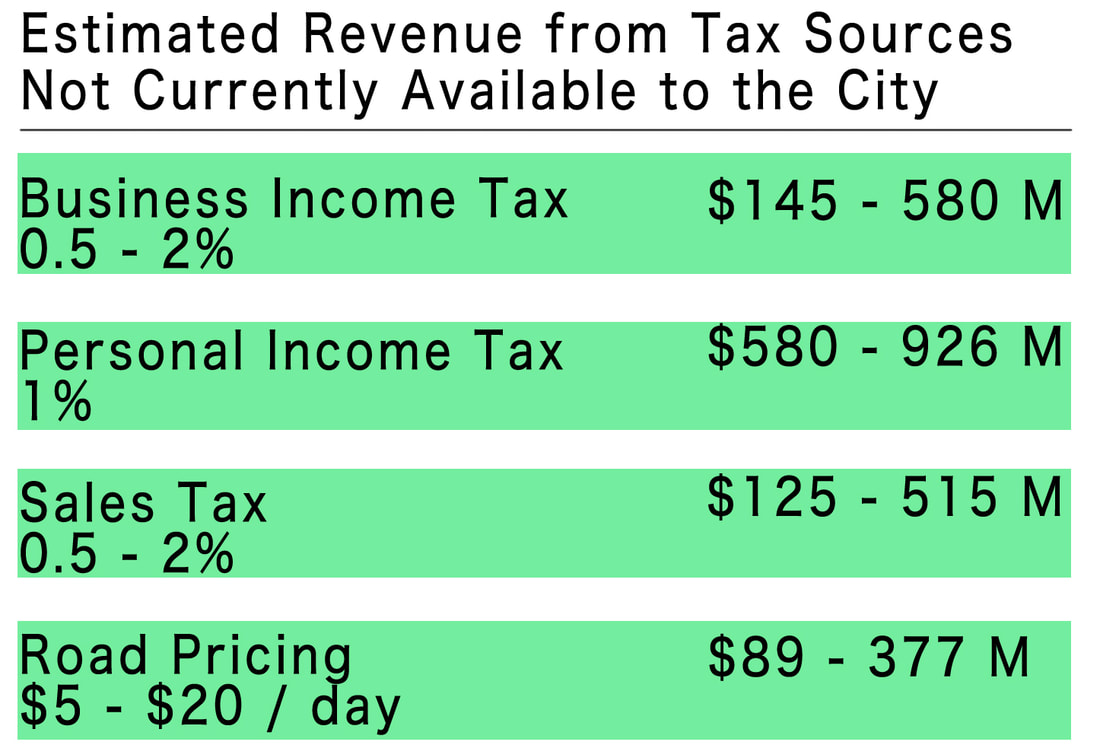

It is important that in the case of shared cost arrangements, the city be protected from unilateral provincial decisions reducing such payments. • The city should have direct access to existing progressive revenue sources that grow with the economy, taxes such as sales and income tax to be spent at the discretion of the city. • The city should be given a dedicated portion of these existing taxes commensurate to current provincial contributions to the city’s operating budget and the power to levy its own additional sales and income taxes if necessary. |

|

• The city should be given full control of the property tax system including the power to establish assessments, classes of property, and apportionment of tax burdens to different classes of property (such as to protect small business.) The city should control all property taxes raised in the city.

• Responsibilities or expenditures should only be downloaded to the city from the province with the consent of the city, after adequate notice has been given in the budget cycle and revenues are transferred to city control sufficient to offset any additional costs to the city. • Arrangements for the funding of shared responsibilities must be worked out. The city could receive block funding from the federal and provincial governments equal to the amount spent on those programs in Toronto, increased annually according to some fair formula based upon, perhaps, increases in the cost of living. Or, preferably, the province and city could determine the amount transferred to the city for |

"Tax sharing, whereby

|

these programs, and designate that amount as a municipal revenue source, apply an annual cost of living increase, then collect and remit it to the city.

Either way, it is essential that these revenues be stable, predictable, permanent arrangements that can only be changed or revoked with the assent of the city.

Either way, it is essential that these revenues be stable, predictable, permanent arrangements that can only be changed or revoked with the assent of the city.

Why Doesn't the City Use More of the Tax Powers It Already Has?

Study after study has shown that the city of Toronto does not have a spending problem; it has a revenue problem.

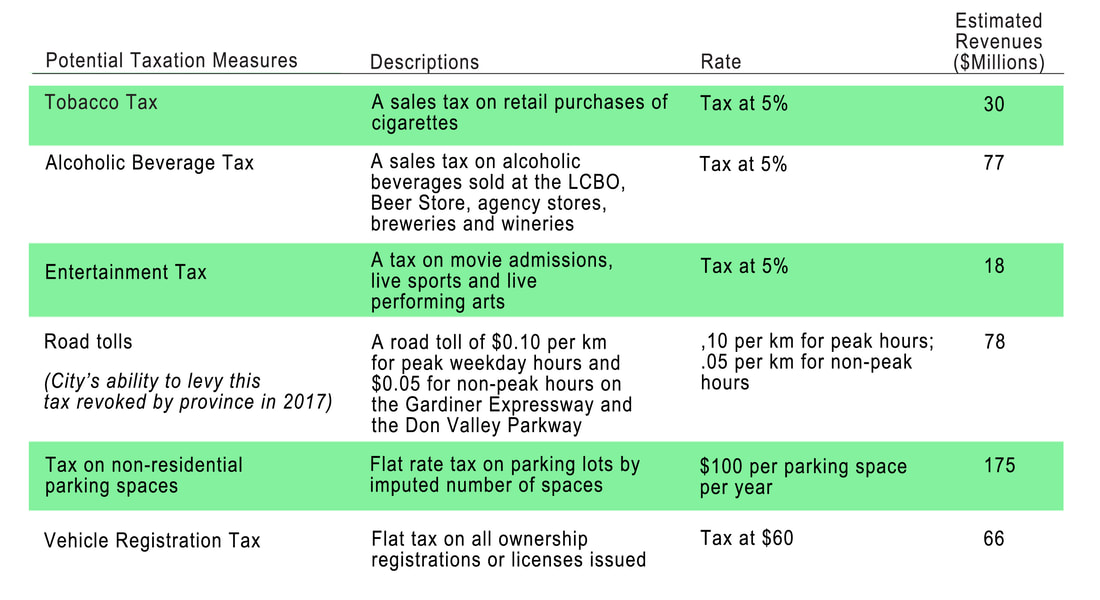

Under the City of Toronto Act, the city has provincial permission to raise a small number of additional taxes: on tobacco, alcohol, places of amusement, vehicle registrations and parking.

Under the City of Toronto Act, the city has provincial permission to raise a small number of additional taxes: on tobacco, alcohol, places of amusement, vehicle registrations and parking.

|

Together, it is estimated that taxes in all of these categories combined, would net the city about $400 million--nothing to sneeze at, but a far cry from the revenues needed to address the city's financial problems. It's not enough to make up for the existing $3 billion gap between revenue and operating expenses, a number which will grow in coming years. Nor does it address the tens of billions of dollars needed to keep city infrastructure in a good state of repair. And as new taxes on top of existing taxation, they would not correct the current situation whereby the city contributes some $13 billion a year more in taxation to senior levels of government than it gets back. |

While some additional city taxation may be desirable and even necessary, without access to large scale taxes such as sales tax, income tax and road tolls, it is difficult to see how city needs can be financed.

FINANCES

|

The city requires provincial approval to borrow money, a duplication of effort that is time consuming and costly. As well, some other financial matters require provincial approval. • The city should have exclusive authority to manage its financial affairs including borrowing funds, budgeting for a short-term deficit, and tax increment financing with respect to property taxation. • The city should have the ability to use new financial tools, including self-financing powers such as municipal bonds, as required. |